AI is changing how software gets built. Writing code is faster. Getting something working is easier. What hasn’t changed is how hard it is to decide what’s worth building and why.

As implementation speeds up, decision-making becomes a scarce skill. This learning path is how I’m choosing to invest in that skill.

Why relevance looks different now

For a long time, being effective meant being good at execution. Learn the framework. Ship features. Move fast. That still matters — but it’s no longer enough on its own. When tools can generate working code quickly, the value shifts upstream.

The real leverage is in framing problems, making tradeoffs, and deciding where effort is justified & that’s the gap I’m working on.

Why design-driven development

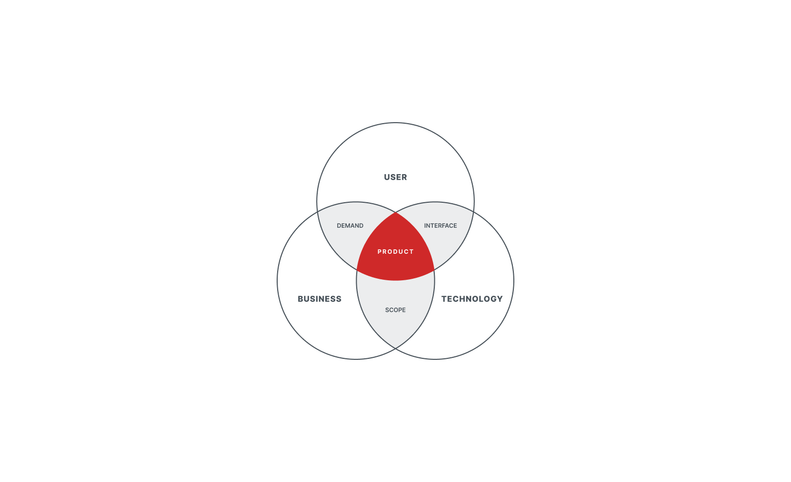

Business

Represents economic reality. Focused on viability, constraints, and outcomes — budgets, timelines, growth, and sustainability. This perspective keeps the work grounded in what the product needs to survive and scale.

User

Represents the people using the product. Focused on clarity, usability, accessibility, and overall experience. This perspective ensures the product is useful, understandable, and actually solves a real problem.

Technology

Represents what’s feasible and maintainable. Focused on implementation, performance, reliability, and long-term health of the system. This perspective turns ideas into working software that can evolve over time.

Design-driven development works because it forces these perspectives to be considered together, before decisions harden into code.

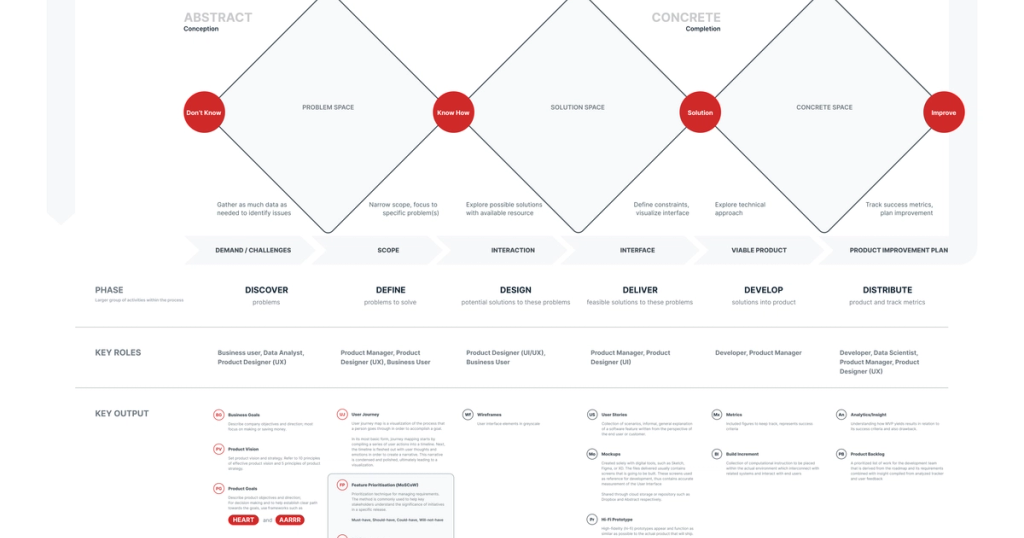

It emphasizes:

- Understanding the problem before jumping to a solution

- Working through uncertainty instead of ignoring it

- Balancing user needs, business goals, and technical constraints

- Making clearer tradeoffs before execution starts

What I’m using to learn

This learning path isn’t theoretical. I’m grounding it in real systems and products that I actively build and maintain.

Each project exists for a specific reason, and each one lets me practice a different aspect of Technical Product Management.

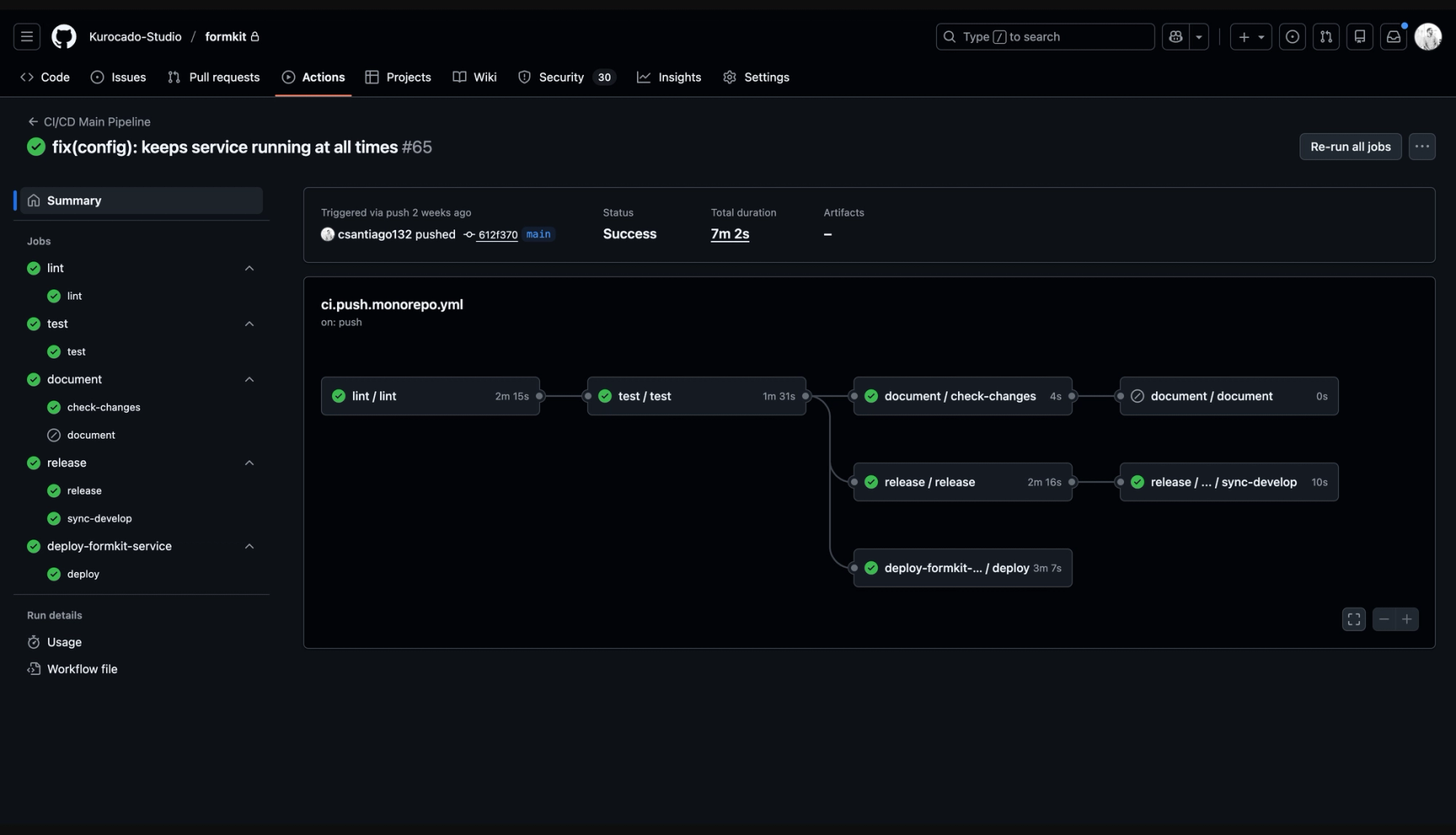

The Platform — stable foundation for multiple products

The Platform is a shared engineering foundation built to support multiple products. This is not an MVP — it’s a stable system that everything else depends on.

What makes it valuable as a learning surface is that it forces platform-level decision-making:

- How shared infrastructure scales across products

- When abstraction helps versus when it creates overhead

- How decisions today affect speed and flexibility later

This is where I focus on long-term thinking, reuse, and systems design — the kinds of tradeoffs that only show up when multiple products depend on the same foundation.

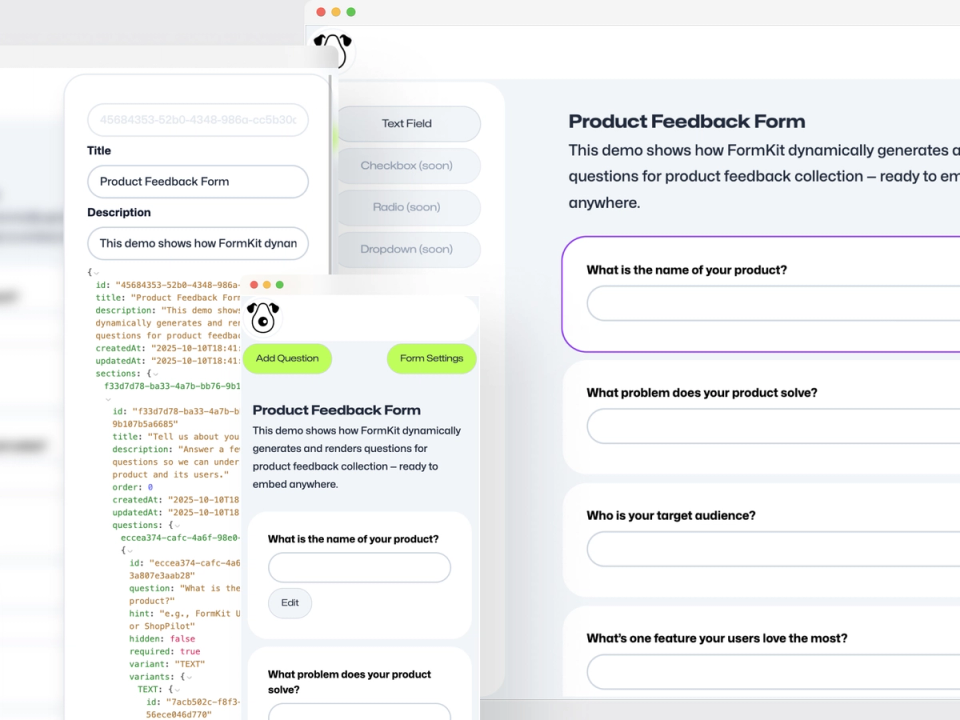

FormKit (Product A) — front-end engineering and accessibility

FormKit is where I focus more heavily on front-end execution and accessibility.

I intentionally built an MVP first to get the idea out, validate the core concept with a working renderer, and document the thinking behind it in a case study.

The product itself surfaces real complexity:

- Schema-driven rendering and state management

- Validation and interaction edge cases

- Accessibility as a first-class constraint, not an afterthought

This is where I focus most on front-end engineering quality and inclusive design. Product decisions here directly affect real users, which makes tradeoffs around scope, usability, and correctness very concrete.

SystemHaus (Product B) — UX and design decision-making

SystemHaus is where I focus more on UX design and interaction decisions. Like FormKit, it started with a clear concept and an MVP mindset. In this case, validation happens through a walkthrough video that demonstrates the system, the problems it’s solving, and how it fits into a real workflow.

Design systems sit at the intersection of design, engineering, and product. Small decisions around tokens, theming, defaults, and structure have outsized impact on how teams work and how products feel. This project gives me space to practice UX-driven product thinking, especially in areas where there isn’t a single correct answer — only tradeoffs.

Together, these projects give me different surfaces to practice the same core skill:making good decisions before and during execution.

The case studies exist to document those decisions — not just what shipped, but why it made sense at the time.

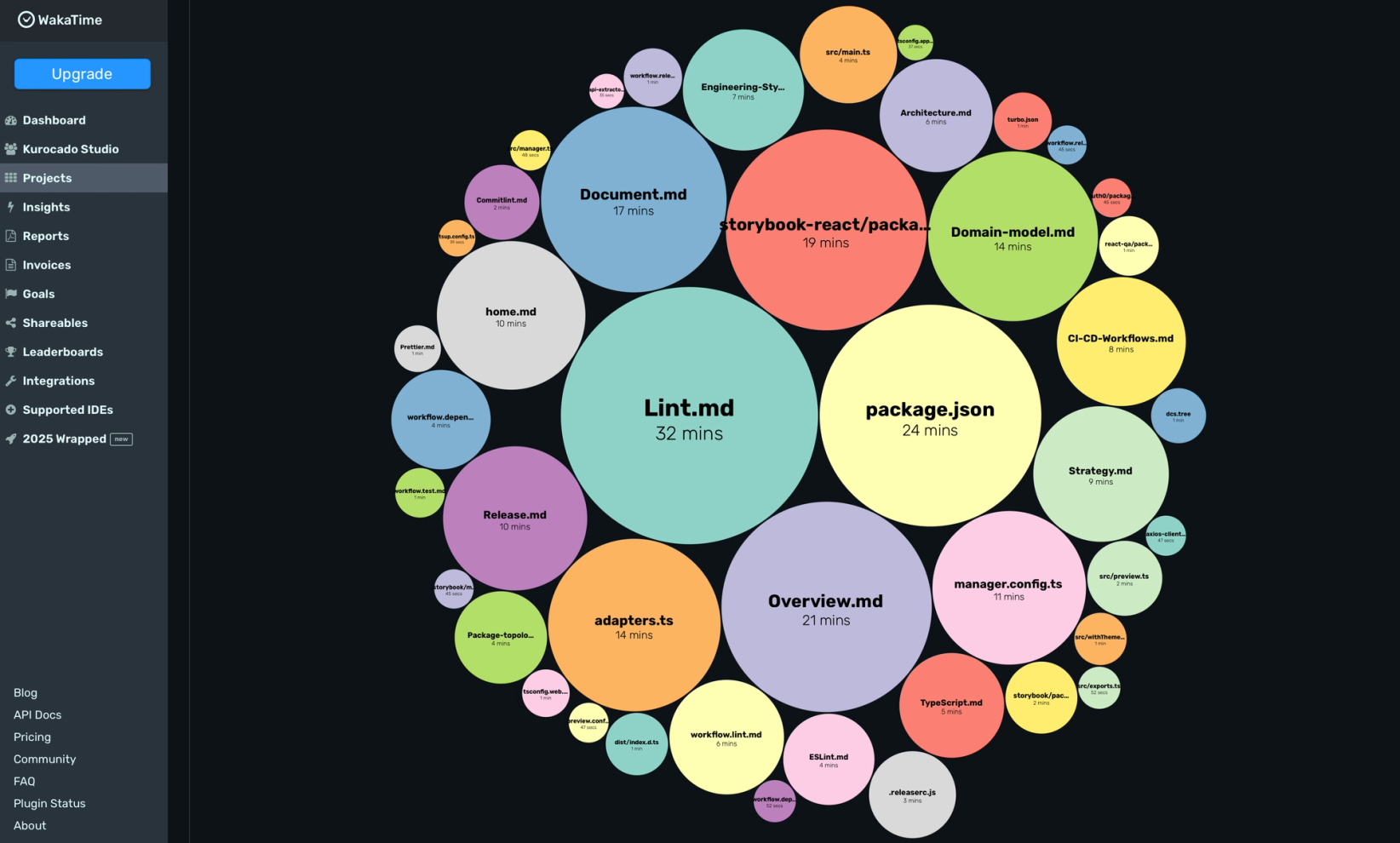

WakaTime — time tracking for learning, reporting, and billing

I also use WakaTime as part of this learning setup.

At a basic level, it helps me understand where my time actually goes across these projects — not where I think it goes. That visibility matters when you’re trying to be intentional about how you learn and where you invest effort.

More importantly, it creates a paper trail.

If any of these products move toward Open Collective or sponsorship, time tracking becomes part of responsible stewardship:

- Transparent reporting of effort

- Clear separation between platform work and product work

- A foundation for billing or sponsorship accountability if the projects grow

What I’m actually learning

This is what Technical Product Management looks like in practice for me: working at the intersection of engineering and product, turning ambiguity into direction, making decisions with real technical context, and aligning work around intent rather than tasks.

References & influences

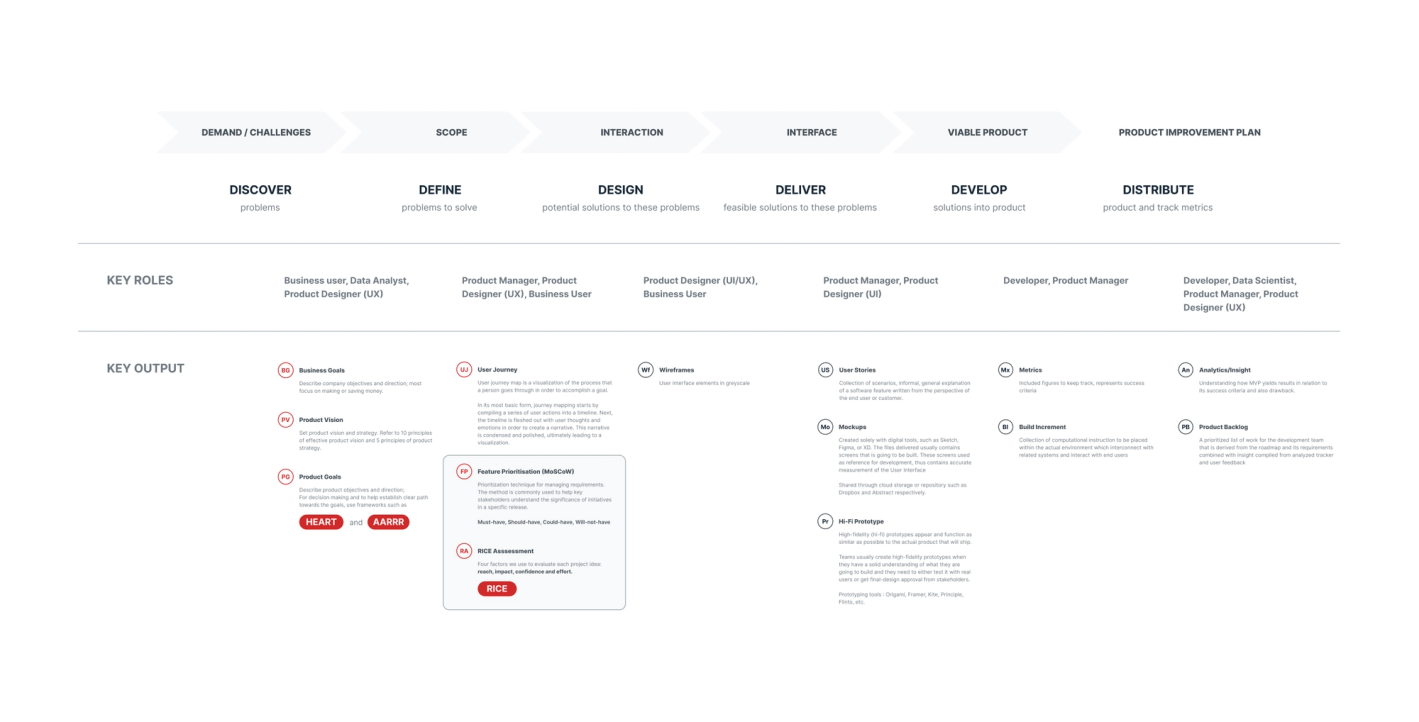

This learning path isn’t based on a single framework. It’s informed by established work in design, UX, and product thinking that I’m actively studying and applying.

- Design Council — The Double Diamond framework for innovation

- ISO 9241-210 — Human-centered design for interactive systems

- McKinsey — The business value of design

- Google Research — Measuring the User Experience on a Large Scale

- AARRR Metrics Framework - See Metrics Framework

- Design-driven product development overview (Business / User / Technology pillars) Compiled by Fares Farhan, CC BY